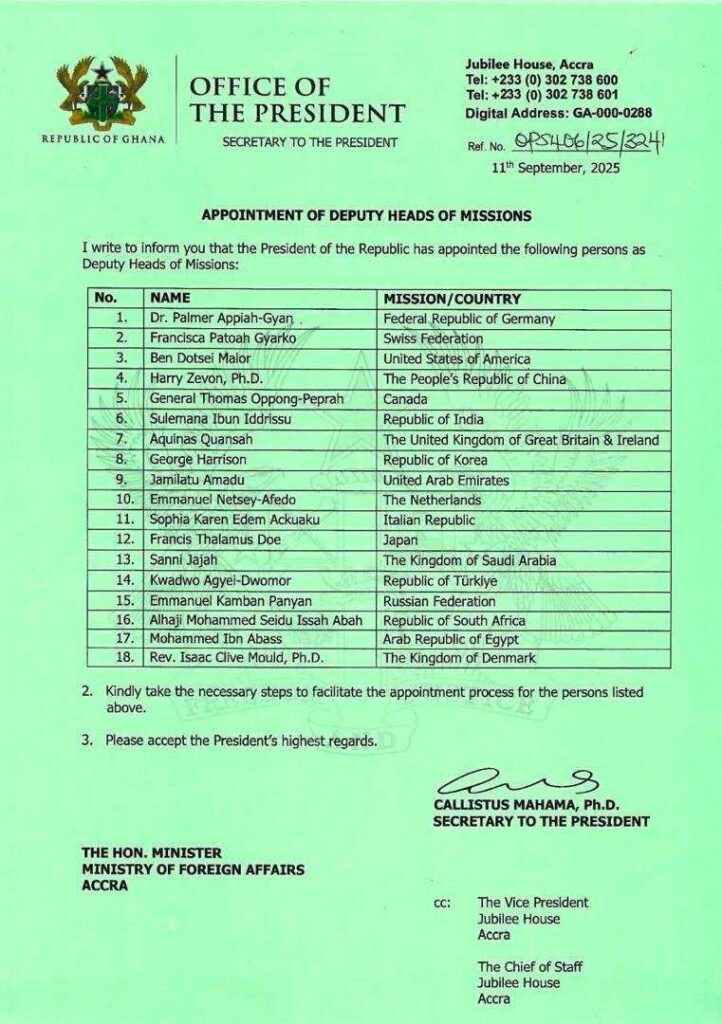

President John Dramani Mahama has appointed 18 new Deputy Heads of Mission to Ghana’s embassies and high commissions across the globe in what government insiders describe as a “strategic move to strengthen Ghana’s diplomatic capacity and renew its global image.” The appointments, confirmed in a letter signed by Dr. Callistus Mahama, Executive Secretary to the President, include distinguished figures such as former Chief of Defence Staff General Thomas Oppong-Peprah and ex-Presidential Spokesperson Ben Dotsei Malor. The new deputies are expected to assist ambassadors and high commissioners in executing Ghana’s foreign policy objectives, ensuring continuity in representation, and advancing trade, security, and cultural diplomacy.

The move signals a renewed emphasis on professional diversity within Ghana’s foreign service, reflecting Mahama’s broader goal of aligning diplomacy with national interests. With today’s interconnected world marked by security concerns, shifting economic alliances, and heightened global competition for investment, Ghana’s government appears intent on fielding a robust team that combines political experience, defense insight, and communication expertise.

For instance, Ben Dotsei Malor’s background in international communication and media management positions him to strengthen Ghana’s public diplomacy efforts in key capitals such as Washington, D.C. His years of service at the BBC and the United Nations have built him a reputation for strategic communication, which could prove invaluable as Ghana seeks to attract foreign investors and project a stable national image abroad. Meanwhile, General Oppong-Peprah’s appointment introduces a strong defense perspective at a time when West Africa faces escalating security challenges—from terrorism in the Sahel to maritime threats in the Gulf of Guinea. His experience leading Ghana’s military could enhance cooperation on peacekeeping missions and defense diplomacy, where Ghana continues to play a pivotal regional role.

This reshuffle matters not only to Ghana but to Africa more broadly. In an era where smaller states must maximize their diplomatic presence, the continent’s nations are realizing the importance of capable deputies in embassies to ensure consistent representation even when ambassadors rotate or are unavailable. Diplomacy is no longer a ceremonial pursuit—it is an instrument for economic partnerships, technology transfer, and crisis management. Ghana, seen as one of West Africa’s most politically stable nations, has increasingly positioned itself as a voice for African perspectives in global governance. By investing in its second-tier diplomatic leadership, Ghana strengthens its influence and operational resilience in multilateral forums such as the United Nations and the African Union.

Historically, Ghana has maintained one of the most respected diplomatic corps in sub-Saharan Africa, a tradition dating back to Kwame Nkrumah’s post-independence years when the country became a hub of Pan-African diplomacy. However, over the past decade, the foreign service has faced logistical and budgetary challenges, including staffing shortages, delayed postings, and limited training. These new appointments could mark an attempt to reenergize the service and restore its capacity to project Ghana’s image effectively. The balance between career diplomats and politically appointed individuals has always been delicate, but this round of appointments may indicate a pragmatic mix—where political insight and professional skill complement each other.

Nonetheless, questions linger about transparency and meritocracy. Critics within the foreign policy community argue that political loyalty still plays a role in diplomatic postings, which could undermine professionalism if not managed carefully. Career diplomats often advocate for merit-based promotions to ensure institutional continuity and efficiency. To maintain credibility, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs will need to ensure these deputies receive adequate training and orientation on international law, consular protocol, and economic diplomacy.

Public reaction to the appointments has been mixed. Supporters view it as a positive step toward reinforcing Ghana’s embassies and improving responsiveness to the Ghanaian diaspora’s needs. On social media, many highlighted the symbolic importance of seeing figures like Oppong-Peprah and Malor, known for discipline and communication excellence, stepping into diplomatic roles. Others, however, have expressed concern that political appointees may overshadow career officers who have risen through the ranks. Policy analysts like Dr. Kojo Asante of the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) note that the true test of these appointments will be the outcomes they produce—stronger trade relationships, improved citizen services abroad, and better representation in multilateral negotiations.

Beyond domestic implications, the appointments also tie into Ghana’s regional and global ambitions. The country has long served as a peace broker in West Africa, contributing troops and mediators to conflicts in Mali, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Strengthening its diplomatic apparatus could reinforce Ghana’s credibility as an anchor of regional stability and a partner to both Western and African institutions. Furthermore, with increasing migration and global economic interdependence, Ghanaian missions are handling more consular cases, investment inquiries, and cultural exchanges than ever before. Well-prepared deputies will be essential in sustaining these operations effectively.

Economically, diplomacy is becoming a key driver of trade and investment partnerships. Ghana’s growing sectors—energy, mining, agriculture, and technology—require external engagement and international visibility. Competent deputy heads can support ambassadors in negotiating agreements, facilitating business forums, and promoting Ghana’s participation in global trade networks. For instance, Ghana’s membership in the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) presents both opportunities and challenges that require diplomatic skill to navigate, especially in balancing local industrial interests with continental obligations.

This story matters because it reflects a broader reality in African governance: the need to professionalize diplomacy as an instrument of development and security. Many African states struggle to maintain an effective global presence due to resource limitations and leadership gaps. Ghana’s latest appointments could serve as a model for building more resilient, multitiered diplomatic systems that leverage expertise across various domains—military, communication, and policy.

A relevant image to accompany this story would show Ghana’s flag alongside the national flags of major diplomatic partners, symbolizing renewed international engagement and the strength of its foreign representation.

As Ghana recalibrates its foreign policy priorities, these appointments will be closely observed both at home and abroad. Success will depend on how well the new deputies collaborate with ambassadors, engage host nations, and translate diplomatic presence into tangible benefits for Ghanaians. If executed effectively, this could mark a turning point in how Ghana projects itself globally—not just through ambassadors, but through a capable, dynamic team of deputy leaders ensuring the country’s voice is heard wherever its interests lie.

Read Also: Mahama Promotes 21 Judges Amid Controversy