Cedi appreciation has become the centre of a growing dispute in Ghana’s retail markets after the Ghana Union of Traders’ Associations (GUTA) accused some traders of deliberately refusing to reduce prices despite falling input costs. The disagreement goes beyond market ethics; it raises deeper questions about how macroeconomic gains are transmitted to households and whether recent economic improvements are being fairly shared.

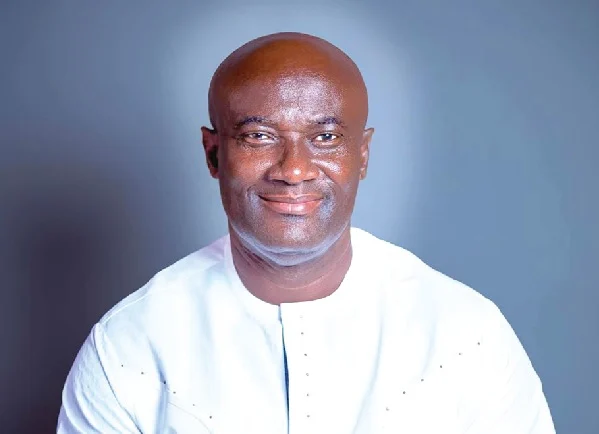

GUTA President Clement Boateng’s comments reflect public frustration at a time when the cedi has strengthened noticeably, easing import costs and improving margins for many businesses. Yet for consumers, especially low- and middle-income households, daily prices for essentials such as bread and household goods remain stubbornly high. This disconnect has turned cedi appreciation into a litmus test for price discipline and market competitiveness.

How cedi appreciation should affect prices

Under normal market conditions, cedi appreciation reduces the cost of imported inputs, including raw materials, packaging, fuel-related logistics, and finished goods. For an import-dependent economy like Ghana’s, a stronger currency should gradually translate into lower wholesale prices and, eventually, reduced retail prices.

Traders benefit first. Lower replacement costs improve cash flow, boost margins, and ease pressure on working capital. Over time, competitive forces are expected to push businesses to pass part of these gains on to consumers to retain market share. This is the mechanism GUTA believes is being deliberately stalled by some traders.

Despite the macroeconomic logic, cedi appreciation does not automatically guarantee price reductions. Several factors slow transmission. First, traders may still be selling old stock purchased at higher exchange rates, making immediate price cuts financially painful. Second, high operating costs, rent, utilities, taxes, and credit, can offset currency gains.

However, GUTA’s criticism targets a narrower group: traders who continue charging high prices even after restocking at lower costs. According to Mr Boateng, this behaviour is less about economics and more about attitude, market power, and profit maximisation in segments where competition is weak.

What this means for businesses

For businesses, cedi appreciation presents both an opportunity and a risk. Traders who reduce prices strategically can increase turnover, attract price-sensitive consumers, and expand market share in a highly competitive retail environment. As Mr Boateng noted, most businesses survive on volume rather than hoarding stock.

On the other hand, traders who resist price adjustments risk losing customers to more responsive competitors. In an era of rising consumer awareness and tighter household budgets, pricing rigidity can quickly erode brand loyalty and long-term profitability. The message from GUTA is clear: refusing to adjust prices may hurt traders more than it helps them.

For households, cedi appreciation should, in theory, translate into improved purchasing power. When prices fall, disposable income stretches further, easing pressure on food budgets, transport costs, and basic living expenses. This is particularly important as many families are still recovering from the inflationary shocks of recent years.

The failure to reflect currency gains in consumer prices delays this relief. It also undermines public confidence in economic recovery narratives, making households sceptical about official data on falling inflation and improving macroeconomic stability. In practical terms, families feel excluded from gains they are told exist.

Market competition as the real enforcer

Rather than regulation, GUTA believes competition will ultimately enforce price discipline. In open markets, consumers gravitate toward sellers offering better value. Traders who refuse to respond to cedi appreciation by adjusting prices may find themselves sidelined as rivals sell faster, restock sooner, and grow stronger.

This dynamic is already visible in some sectors, where price moderation has contributed to slowing inflation. According to Mr Boateng, these reductions are happening “across board,” even if pockets of resistance remain.

The debate around cedi appreciation is ultimately about trust, trust between traders and consumers, and trust in how economic improvements are shared. If currency gains consistently fail to reach households, public support for market reforms weakens, and social tension rises.

As inflation slows and the cedi stabilises, the next phase of Ghana’s recovery will be judged not by exchange-rate charts but by market prices. Whether traders respond constructively may determine how quickly economic confidence is rebuilt at the household level.

Geopolitical tensions set to drive commodities and capital flows in 2026, MIIF Says